More Seniors are in Debt: An Unintended Consequence of Low Interest Rates

When interest rates are especially low—like today—Americans have a greater incentive to borrow and spend. The reasons are many. Buy a car, a home or a new appliance. Americans also borrow to pursue more education or take a vacation. All this contributes to a growing economy.

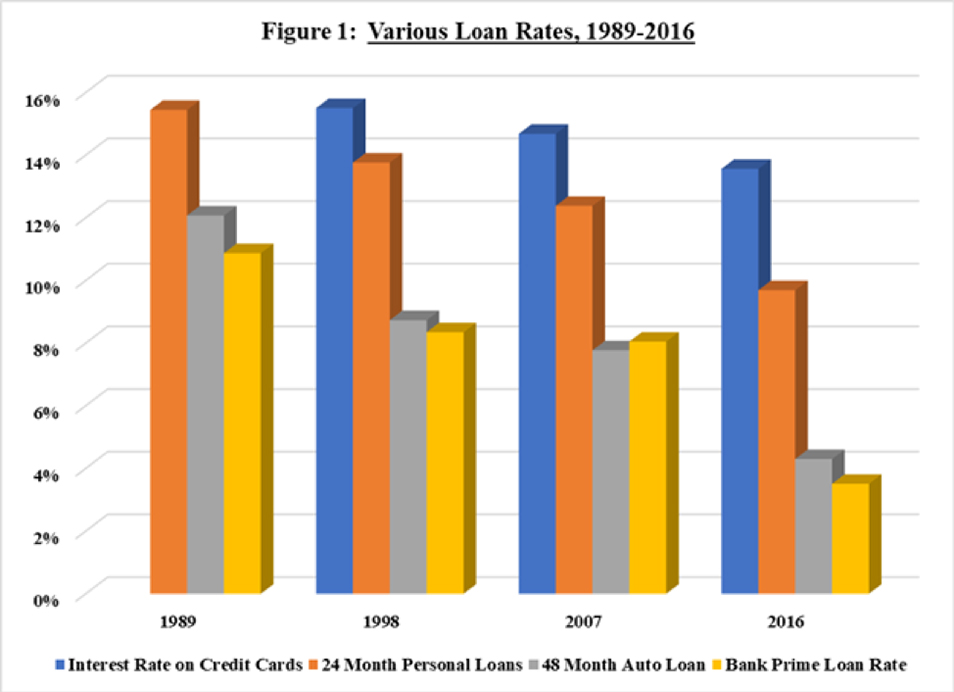

From the 1980s until about 2010, interest rates were on a downward trend. Since 2010 they’ve remained historically low. For example, in 1989 the interest rate on 24-month personal loans in the United States averaged 15.4%. 48-month auto loans averaged 12.1%, and the bank prime rate averaged 10.9% (see figure 1).

By 2016 these rates had declined to 9.7%, 4.3%, and 3.5%, respectively. Data on average credit card interest rates aren’t available for 1989. But in 1998 rates were 15.5%. They declined to 13.6% in 2016.

An unintended consequence of low interest rates is that a greater percentage of retirement-age households now carry a credit card balance or have other debt, such as auto loans and installment loans. This debt creates an added financial burden for retirees, many of whom live on a fixed income.

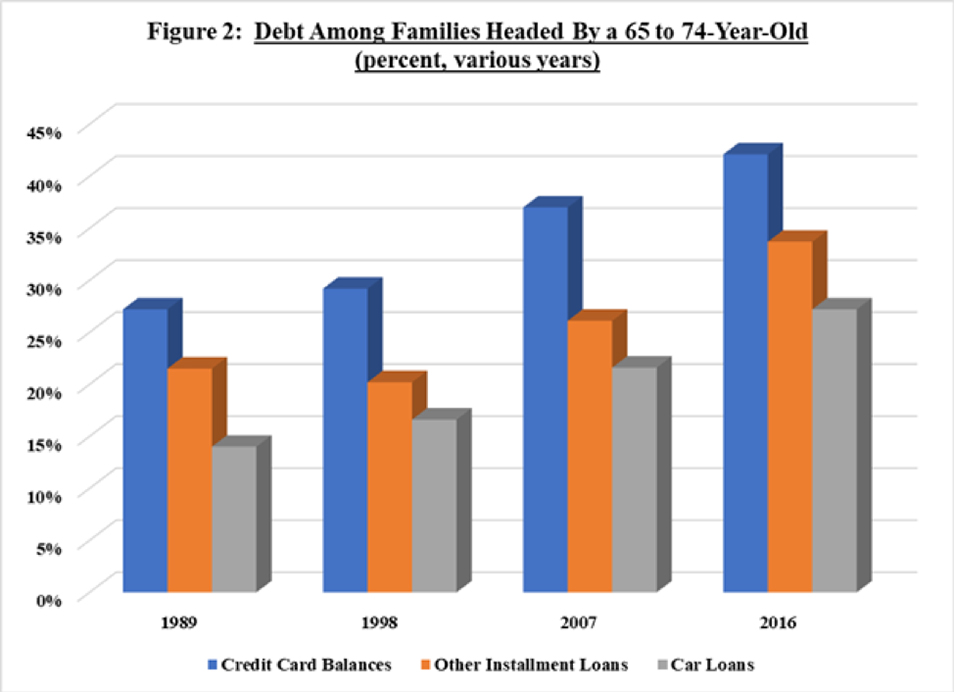

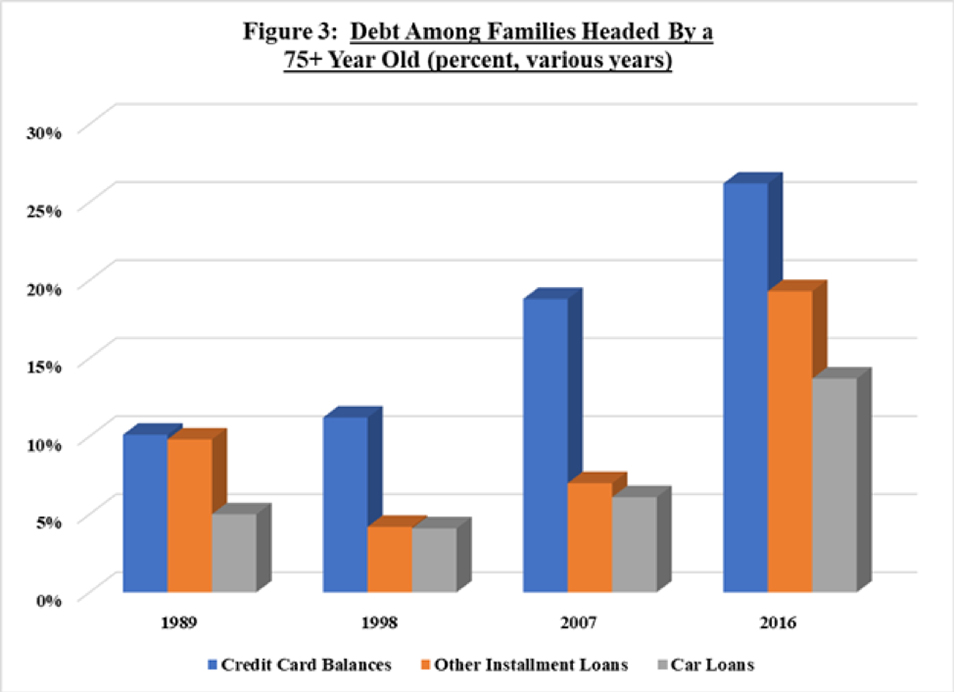

In 2016, 27.2% of households headed by a 65-to-74-year-old had an auto loan, compared to just 14.0% in 1989. Similarly, 33.7% had other types of installment loans compared to 21.5% in 1989. And 42.1% carried a credit card balance, compared to 27.2% in 1989 (see figure 2). The increase is even more stark among households headed by someone age 75 or older (see figure 3).

Lower rates are usually good news for borrowers. But taking on debt may not be a good idea if you are retired or near retirement, especially if you’re planning to rely primarily on your savings to fund your retirement.

Low interest rates make it harder to save, undercutting a traditional savings ethic based on the time value of money. But retirees who have guaranteed income from a lifetime annuity may be in a much better position to take advantage of low interest rates to help with pricey home repairs or perhaps even necessities like a car.